Sometime last week, while swimming through cat videos and cooking tutorials on Instagram, I found Bollywood royalty Saif Ali Khan at an indoor net-practice facility. In the video, he is standing next to his seven-year-old son, Taimur, educating him about English cricket clubs. Taimur, probably still new to cricket, reaches for the closest equivalent. In his adorable, squeaky voice, he chirps, “Like MI (Mumbai Indians)?”

Saif’s face, in that moment, is precious. He looks into the distance, fumbles through “Sussex” and “Worcestershire” like an old historian trying to remember street names from the stone age, before grabbing the familial parachute: “Your grandfather captained Sussex.”

It doesn’t take much to make me feel old these days, but this 10-second clip left me feeling ancient. See, Taimur isn’t wrong. Mumbai Indians is technically a cricket club. But what threw Saif - and me - off is the immediate recall value of an IPL franchise for a kid.

For a lot of us dinosaurs, English counties were part of the cricket curriculum. You learnt of them as you were learning about the game. Botham and Viv played for Somerset, Donald and Pollock for Warwickshire, Akram and Atherton for Lancashire. The world’s best sought out the county championship every year - sometimes to maintain rhythm, other times to fix bugs. Many top cricketers still go.

On the other hand, we have cast the IPL as cricket’s annual trip to Las Vegas. It’s a drunken indulgence, a two-month junk food buffet nestled between the real, tough routine of international cricket. Delicious? Absolutely. Nutritious? Moving on...

In hindsight, we may have slightly underestimated the IPL’s ambitions.

A couple of weeks back, The Telegraph reported that Sunrisers Hyderabad have submitted a bid worth $65 million for a controlling stake in Yorkshire County Cricket Club. Founded in 1863, Yorkshire CCC is one of England’s oldest county teams. Over the last few years, they have incurred losses worth millions of pounds, and now stand on the brink of bankruptcy without an injection of foreign cash. 1

This isn't a one-off, either. The England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB), sensing which way the wind is blowing, or perhaps just following the scent of money, has opened its arms to private investment. They're offering 49% ownership stakes in each of the eight franchises of The Hundred, their shiny new limited-overs competition that answers the question - “What if T20 cricket, but on cheaply-sourced magic mushrooms?”

Mumbai Indians, as you’d expect, are going after London Spirit, a team based out of Lord’s and currently owned by the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), founded in 1787 and one of the world’s most prestigious clubs. If the bid goes through, London Spirit will probably be renamed to MI London, becoming a sister franchise to MI Cape Town and MI New York. By the summer of 2025, IPL franchises could be pulling the strings of top-tier teams in India, England, South Africa, and America. Stack all these leagues together, and you've got a cricket colossus occupying about 60% of the annual calendar.

This has other long-term implications too, from player contracts to player movement. As it is, the IPL doesn’t allow contracted Indian players to play franchise cricket outside India. With financial control over multiple leagues, they could soon be deciding whether Jofra Archer or Travis Head can play in a particular tournament, pending approval from Mumbai.

There is monopoly, and then there’s this.

At this point, it is tempting to look very, very suspiciously at Lalit Kumar Modi, architect and biological Dad of the IPL. We’ll get there.

The IPL, funnily enough, wasn’t even Lalit Modi’s first pitch to the BCCI for a franchise cricket competition. Modi had spent a lot of time in the USA and England, and was blown away by the cultural imprint of NBA and Premier League teams. He wanted to create something similar in cricket. A Woodstock equivalent, an entertainment product that went beyond just the sport. But there was a key problem: Michael Jordan and David Beckham were playing at least once every week; Sachin Tendulkar wasn’t. International cricket’s rhythms and structures didn’t allow for it. So, somewhere around 1997, Modi reached out to the BCCI with a plan for a franchise ODI competition. Imagine - Tendulkar and Jayasuriya in one team, multiple times a week. The BCCI saw promise but didn’t want to cede control of the teams, so they let this pass.

Modi returned in 2007. T20 cricket had taken off in England, an inaugural World Cup was about to kick off in South Africa, and India was getting younger. The Indian Cricket League, a rogue league managed by TV moguls and millionaire celebrities, illustrated the infinite possibilities if planning and commitment married ambition.

And when Misbah ul-Haq’s poorly-timed scoop shot landed sweetly into Shanthakumaran Sreesanth's hands, crowning India as T20 world champions, the green light was granted.

Sony Network paid the BCCI $1.026 billion - keep that number in mind - for the TV rights for the first ten years of the IPL.

“The IPLs audacity depended entirely upon Modi and his pin-sharp assumptions about the power of money: that star cricketers would play in the IPL if the price was high enough, and that team owners would pay a high enough price for star cricketers; that big corporations and Bollywood stars would buy teams to massage their egos, and that sponsors would monetise anything if big corporations and Bollywood stars were involved; that the BCCI would leave him alone to run the IPL if the profits were substantial enough, and that he could generate substantial enough profits if the BCCI left him alone; and finally, that this tide of money could be disguised as a tide of cricket, guaranteed to wash over an Indian audience that is forever willing to diagnose itself as cricket-mad…Modi wasn’t the first person to monetise Indian cricket; he was, however, the first to reckon its worth in billions of dollars rather than mere millions.” - Samanth Subramanian, here.

By 2013, the IPL was the centre of the world. Viewership and advertising was rocketing with every passing season, and the tournament was making more money than every international series barring the World Cups. The BCCI, already bold, now became cavalier.

There is a reason for this pitstop: two key things happened that year.

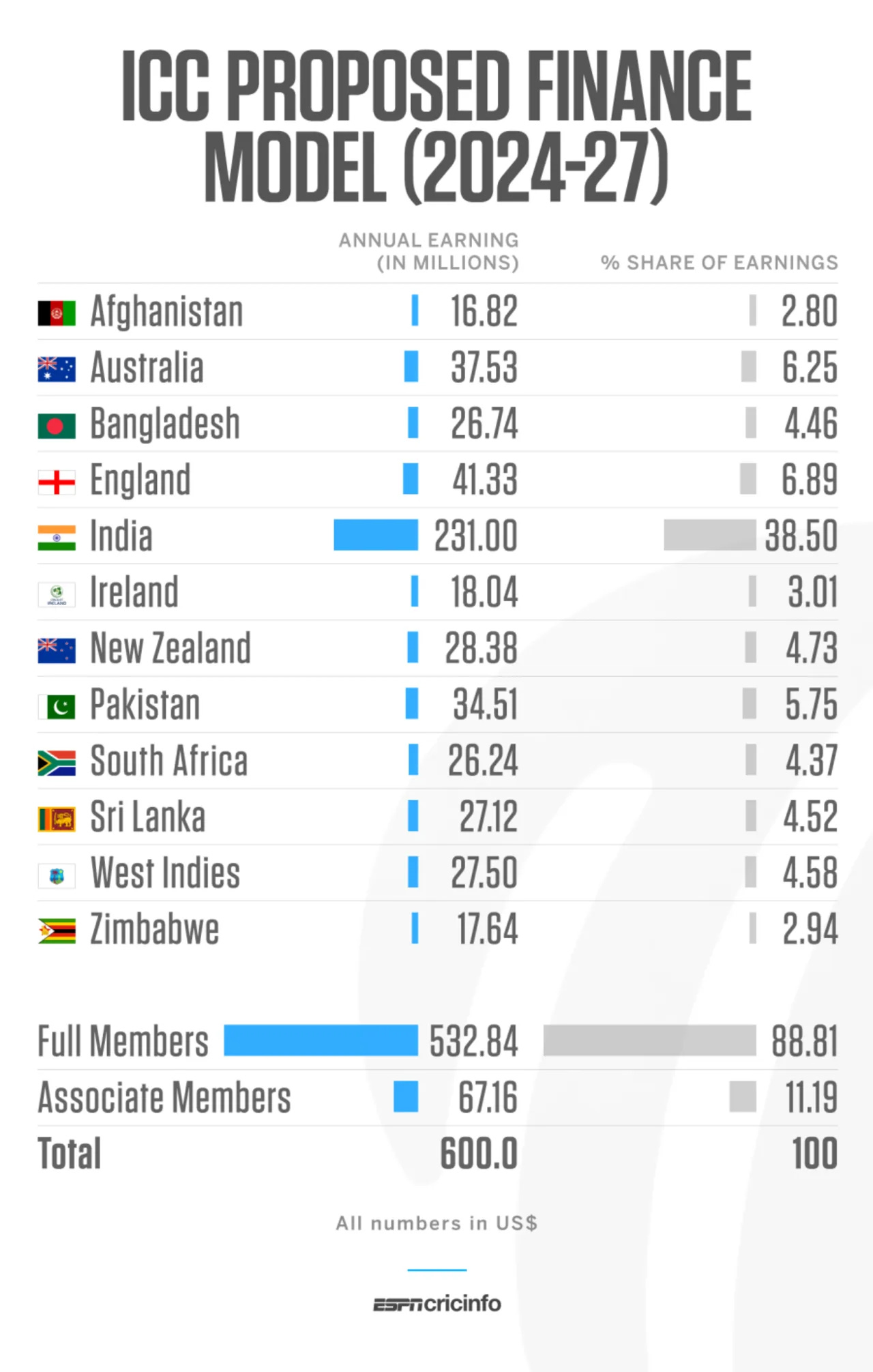

First - the BCCI, along with ECB and Cricket Australia, decided that, since they were bringing the most money back to cricket, they deserve a lion’s share of its annual revenue, with BCCI taking home the biggest chunk. Up until then, the ICC had been egalitarian in its revenue-sharing. That didn’t quite fit with the vibe these guys were looking for.

“Money, it’s a crime,

Share it fairly, but don’t take a slice of my pie” - These guys.

So the Big Three™ took the plan to the top of cricket’s governance, the International Cricket Council. The other, poorer members had no choice but to comply. Sounds very mafia?

Wait for this. The other reason 2013 is important is because Sachin Tendulkar announced his retirement. The farewell party was going to be a major event, a Superbowl equivalent by itself. BCCI looked up their schedule, and found fifteen months of relentless touring: South Africa, New Zealand, England, and Australia, in that order. For a young team beginning to establish themselves, this was an important year of learnings. But Sachin Tendulkar retiring in Cape Town or Auckland? LOL. Voila, West Indies were called over for a two-match Test series. The second of those, Tendulkar’s last, would be played at his home patch in Mumbai. Fair enough, but where did the space for the series come from? At around the same time, India were scheduled to travel to South Africa, to play a four-match Test series. They basically phoned the Cricket South Africa head office, and said, “Listen, can’t do a long trip. Got some plans. Will be late.” and the tour was chopped down to two Tests.

In the third season of the now defunct show, Patriot Act, comedian Hasan Minhaj has an episode called Cricket Corruption. The 26-minute episode is centred around the power-play happening at the top of international cricket, BCCI’s raw lust for influence, and, of course, the IPL. Minhaj even travels to London to speak to Lalit Modi about the tournament.

Modi is proud of what he built, and how he did it, but admits a deep regret. “I ended up building the BCCI a war chest, and that’s very bad for the sport.”

Today, the TV rights deal for the IPL has gone from $1.026 billion - remember? - to $6 billion. INR 48,000 crores. Sounds like a lot of money, but how does that translate to BCCI’s influence?

This is how.

This financial clout is now potent enough to make even England, famously insular and one of the two powers capable of challenging the BCCI, reconsider its position in the sport’s hierarchy. And that’s quite telling.

Thing is, cricket isn’t just an English invention, it’s a distinctly English activity. The aesthetics, the tempo, the rules - this thing was designed for leisurely afternoons in village parks. With regular breaks for a cup of Earl Grey, of course. Even 150 years on, many of its original traditions persist, including the tea-break bit. The Marylebone Cricket Club still writes and maintains the official rulebook, and Lord’s still carries the moniker of The Home of Cricket.

Until 1993, the sport was run from England. Even the ICC operated out of Lord's. But in the last three decades, the rise of limited-overs cricket and franchise tournaments, combined with the BCCI’s ability to leverage its population as an asset, has given Indian cricket an advantage that no other country can ever match. While England still holds an important place in cricket's psyche, and they’re incredibly weird about it, the commercial power centre has decisively shifted eastward.

And this moment, where one of their major county teams might soon be owned by a business tycoon from India, and their flagship competition is going to be wearing IPL colours, is English cricket not just acknowledging that the sport isn’t theirs to own anymore, but them laying prone at the feet of the BCCI.

At the risk of sounding like I’m about to break into God Save the Queen King, it is not a good sign for the sport if one of its proudest bastions is lowering its guard, leaving an open field for a large, hungry, and powerful army to plant their tents all over the horizon. It was a problem when the ICC had its headquarters at Lord’s, and it is going to be a problem when the son of the Home Minister of the world’s most populated country gets to sit atop the food chain. The official announcement confirming Jay Shah’s ascent to the position of ICC President reported that he had been “elected unopposed”. 2

I love Cricket Australia's response to this power shift. They're championing a Test cricket-priority plan for the next seven years and discussing a fund to ensure their best players aren't tempted to become freelance franchise mercenaries. Significantly, they’re not even considering opening the Big Bash to private investment from abroad.

If the proposed plans in England materialise - the likelihood seems high - this is a tectonic moment for cricket. The IPL is already too influential, with countries forced to play tetris with their schedules to accommodate it. Gifting those franchises a nitrous oxide power boost was literally the last thing cricket needed. But here we are - the BCCI and IPL armed with cheat codes, the rest of us settling down with popcorn to see how far they push this.

Granted, we might still be some way away from the day when Lord’s has Pan Bahaar advertisement hoardings plastered around its stands, but we are getting close to a point when Saif Ali Khan can take Taimur to Lord’s for an MI home game, and the stadium DJ drops Duniya Hila Denge Hum on a posh, champagne-sipping London crowd.

For a team that closed its doors, for twenty-four years, to players born outside the Yorkshire county, the irony is delicious.

Interesting choice of words for someone from that family, but we won’t go there today.