Marcelo Bielsa was miserable. Minutes after his Uruguay team had beaten Brazil to reach the Copa America semi finals, Bielsa sat down for the press conference with the eyes of a man whose favourite student had just failed an exam. His shoulders were slumped, his eyes downcast. They darted across the table, reluctant to meet the reporters’ gazes, as if searching for answers only he could see.

“Football has more and more spectators,” he began, his voice laced with resignation, “but is becoming less and less attractive. No matter how many people watch football, if you don’t ensure that what people watch is something pleasant, it will only benefit the business. Because the business only cares about how many people watch it. But in a few years, the players who deserve to be watched will be less, and the game produced becomes less enjoyable, this current artificial increase in spectators will end.”

For most, Uruguay reaching the semi-finals over an eternal favourite warrants a celebratory air. The weight of that moment seemed lost on Bielsa. If you’re familiar with the colours of the Aurora Bielsalis, this lament was extraordinary only for the occasion, and not for the man.

If you’re unfamiliar, don’t go to Google. Not yet. Google will tell you everything about the Bielsa lore - his tactics, his disciples, his undeniable influence on the game. You’ll find streams of articles on why he’s revered like a prophet living in the hills. But before all of that, let me introduce you to the man they call ‘El Loco’ - Spanish for The Madman - with a brief window into his mind. In 1992, his team, Newell’s Old Boys, lost 6-0 to San Lorenzo. He was miserable then too, but not like how you’d expect a young coach, just starting his journey, to be.

“I shut myself in my room,” he said. “I turned off the light, closed the curtains, and I realised the true meaning of an expression we sometimes use lightly: ‘I want to die.’ I burst into tears. I could not understand what was happening around me. I suffered as a professional and I suffered as a fan. For three months our daughter was held between life and death. Now she is fine. Does it make any sense that I want the earth to swallow me over the result of a football match? The reasoning was brilliant, but nonetheless, my suffering from what had happened demanded immediate vindication.”

Football romantic is too sedate a term for Marcelo Bielsa. He is the dictionary definition of a tragic.

While speaking to reporters at the Copa America, Bielsa was disgusted by the football he was subjected to. Even though the cautious, risk-averse style employed by powerhouses like Brazil and Argentina benefitted his own team, it left him deeply troubled. Across the Atlantic, the European Championships were unfolding in a similar vein – most of the top nations were playing a brand of football so sterile it could cure insomnia. France, a team overflowing with enough attacking talent to field multiple squads, opted for a similarly lethargic approach. Coach Didier Deschamps, a World Cup winner as both player and coach, was asked about this philosophy at a press conference. Surely, a man with such a decorated career could afford to be a little bolder? His response mirrored the uninspired style of his team: “If you want to be entertained, watch something else.”

This raises an interesting philosophical question. Teams like France and Brazil are footballing royalty. Their games are circled on every fan's calendar, their jerseys hold a mythical status. How should these giants define success?

People on the streets will give you a clear idea of what they want and the boundaries of what is acceptable. Brazil won the 1994 Men’s World Cup after twenty-four years of wait, and, by all accounts, played some serious Siestaball to get there. For a nation that expects footballing pre-eminence, this approach was seen more as the breaching of a cultural fault line, and less as the vehicle for a cathartic triumph. You don’t steal just because you’re hungry.

But can we truly blame Deschamps or Carlos Alberto Parreira, Brazil's 1994 coach, for their strategies? Traditionally, teams have been judged on results, not aesthetics. Exceptions like Brazil's '82 squad or the Dutch teams in the ‘70s had to evoke poetry and artistry from the high heavens to stand out despite their empty cupboards. The spotlight has only intensified over time; defeat is met by suffocating scrutiny. Reaching the semi-finals is deemed a failure for the big national teams and clubs. For many, even a runners-up medal is met with disappointment. That question about remembering the second person on the moon sounds revolting at first, but you have to admit, has some truth behind it. Competitive sport works on even finer margins, especially for those sat in important chairs. Deschamps has every right to place a higher premium on the result than the style.

Bielsa's angst stems from this very idea. He abhors the notion of sacrificing principles for mere gold. A glance at Bielsa's managerial CV reveals an absence of big-name clubs, and fleeting stints even with smaller teams. His sole brush with a truly high-profile job came with the Argentina national team, and that too twenty years back.

Throughout his career, Bielsa has demanded absurd levels of fitness and dedication from his players. In his mind, players owe it to the sport and the fans to leave every part of their being on the pitch. During his three-year stint at Leeds United, his training methods earned the nickname Murderball. The directorial board of a team isn’t exempt from his obsession either. Anything from the bathtubs to the parking lot – if it doesn't contribute to peak performance, Bielsa takes issue.

All this makes hiring him a gamble, a race to a breaking point. His players' bodies, his own determination, the club's patience, or the results table - something is bound to snap and crumble. This is why he typically signs one-year contracts. He harbours a deep distrust in the alignment between his vision and a system that is governed by all of a globally popular sport’s idiosyncrasies. And yet, he keeps coming back for more, perhaps because he can't imagine life without coaching, or maybe because his is a hairpin-bend ride of eternal hope and inevitable disappointment. No one loves and loathes football quite like Marcelo Bielsa.

“Football is popular property. Poor people who didn't have money to buy things that made them happy had football, that was free. But now they don't have it anymore. Football is a cultural expression, a way of identification.”

And football keeps coming back to Bielsa. Rarely is a coach as loved across cultures as he is.

**

Marcelo Bielsa was born in 1955, in an Argentina teetering on the edge of a terrifying abyss. One month before his arrival, thirty aircrafts bombed Buenos Aires’ main square. This was the Argentine military’s attempt at a coup against the democratically elected, populist president Juan Domingo Perón. It was called the Revolución Libertadora, and ushered in a period of military dictatorship. By September that year, Perón had to flee the country.

This act became a grim overture to Bielsa's childhood – a turbulent period where Argentina lunged six times between military dictatorship and fragile democracy, with dissent silenced by threats and disappearances.

By 1974, through Operation Codor, a web of state repression across Latin America, the Argentine military began a siege on the republic. Anyone suspected of leftist leanings – students, workers, artists – became prey. They were hunted down, abducted, tortured, and killed. The official count stands between 20,000 and 30,000.

In 1978, as Argentina won their first World Cup to a deafening roar at the Estadio Monumental in Buenos Aires, the city had already plunged into darkness. Political prisoners, handcuffed and thrown into detention centres just a few miles away, were listening to the broadcast on radio as the dictator General Jorge Rafael Videla presented the trophy to the Argentina captain.

A young Bielsa, just twenty-two, inhaled this grotesque tension every day. The “lotus in a muck” metaphor rarely finds a more fitting subject.

If you go to Buenos Aires today, you will find murals in every other street depicting the 1986 World Cup win. Shops are lined with paintings and pictures from that joyous moment when Diego Maradona carried his team and nation on his back and took them to salvation. But no one talks about 1978. Maradona’s World Cup was relief from a time they desperately want to erase from their memories. They try every passing day. Most fail. Today, Argentina has the highest number of psychologists per capita in the world.

There is a story about how Bielsa’s grandfather had an attic full of books, and it made him a bookworm while growing up. Over the years, as his personality has slowly unfurled in public, an insatiable thirst for knowledge and absorption has been a strong motif. He studies reams of video before joining teams, and prepares for his opponents by obsessing over details that would miss the eye of the players themselves.

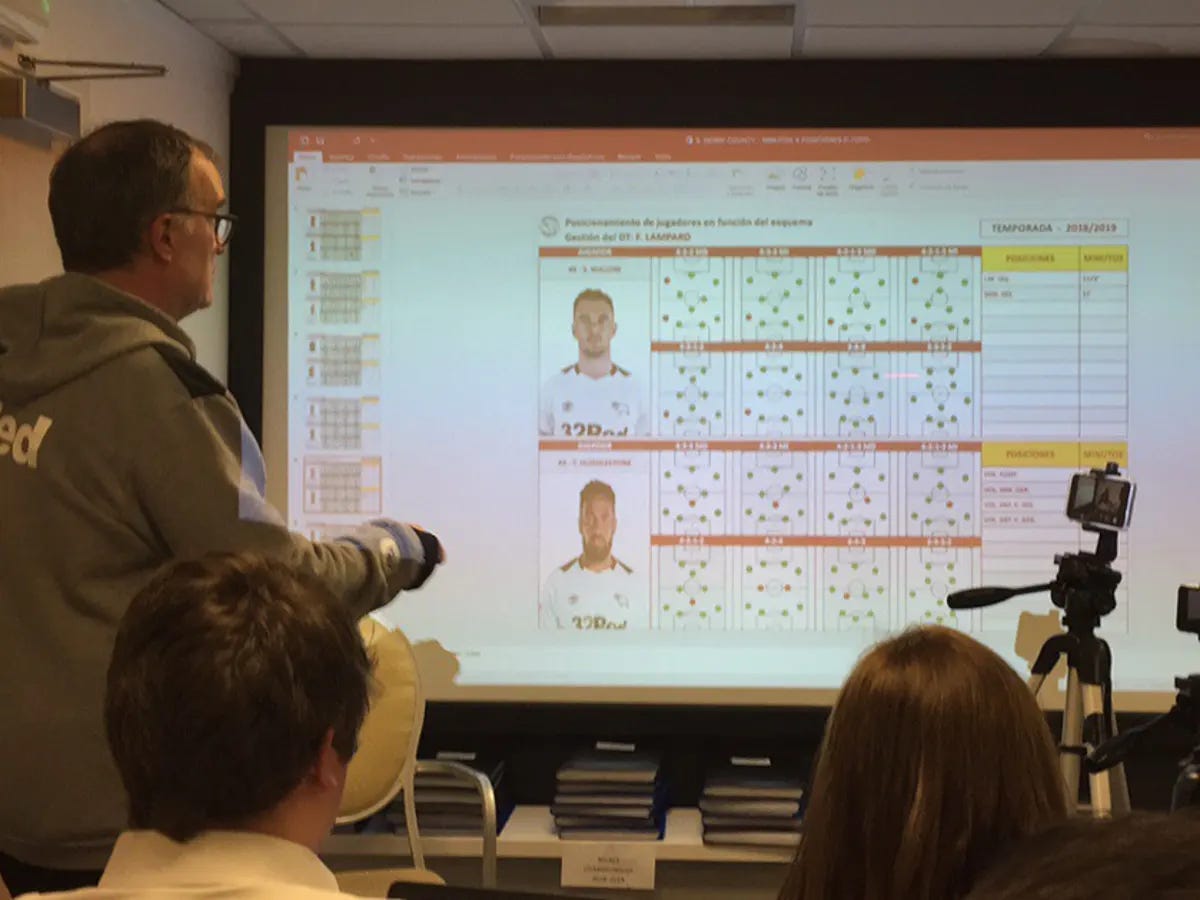

This relentless pursuit reached a comical peak in 2019. During his tenure as Leeds United manager, a scout was caught observing a Derby County training session. The English football fraternity erupted, as if their sport had been sullied by this Latin insurgency. Bielsa, unfazed by the noise, called a press conference. Instead of apologies, he presented each journalist with a thick dossier. It was a comprehensive breakdown of how he analyses every single opponent, treating them like scientific studies. Derby County, he explained, weren't the target of special treatment, just another puzzle he needed to solve.

Spying being illegal, Leeds United were still fined 200,000 pounds, which Bielsa reportedly paid from his pocket. Did he smirk while signing the cheque? One can only imagine.

He has carried that childhood habit of reading into his late-sixties, where he is known to finish one philosophy book every week. He regularly sends his players articles and quotes on WhatsApp, hoping for someone, somewhere to latch onto one of those links and find something worthwhile.

**

Can you imagine telling this man that the FIFA President was recently dancing on “Apna Time Aayega” at the pre-wedding function of the son of Asia’s second-richest man? Try having a conversation with him about the $65 million Real Madrid shelled out for a fifteen-year-old Brazilian prodigy. Or bring up how Apple Inc. and Adidas colluded to ship Lionel Messi from Paris to Miami.

I recently read a thought, saying, “I miss the world when the internet was a place to go sometimes, instead of it being as constant in our lives as electricity.” What a lovely thought, isn’t it? Except, the author had shared this on Twitter. I imagine the irony wasn’t lost on her, as it wasn’t on me. I nodded, clicked on ‘like’, and scrolled along to the next meme.

The title of this essay isn't a random pick. Marcelo Bielsa inhabits a bubble, a fact he's acutely aware of. Even in his tirade two weeks back, he would’ve remembered that his centre-forward plays for Liverpool Football Club, a team owned by an American billionaire. His defensive midfielder plays for a Qatari-funded assortment, and is potentially on his way (hopefully) to Manchester United, co-owned by American and British billionaires, all carrying their operations out of shadowy banks in tax havens. There isn’t an inch of top-level football that is left untouched.

That said, Bielsa is also part of a greying generation who, to some degree, have experienced a time where football felt democratic. When players became members of the community and not Hollywood superstars, when tickets were affordable to the working class, where loyalty thrived, and a player could proudly wear their hometown club's colours throughout their career. This was a time before clubs in glittering European capitals started poaching young talents from Peru and Ivory Coast, relegating them to reserve teams and benches, and snuffing out all creativity and expression out of them in the name of victory.

His fight may be a lost battle, perhaps one he never truly had a chance of winning. Yet, Bielsa’s bubble is a sanctuary, a meadow amidst an industrial sprawl. At times, it is also a necessary mirror for a sport that pretends to be much cleaner than it is.

That philosophical question between him and Deschamps has two ends: one dictated by rationale and reality, and another painted by romance and purity. Bielsa has planted his flag firmly on one side. And he may be the only one of any significance left standing there.

You straddle this line between sports and politics and humour so beautifully, Sarthak. What a lovely profile of Biesla. There is a book of essays that is running towards you with every article you write.

Magnificient !

A great homage to one of the greatest lover of the game. As a Mourinho-ista, an adoring fan of Jose Mourinho, the sharp contrast, and yet the pleasant likeliness between these two figures, both calling out the increasing commercialization of the game, strikes at me. Bielsa, deserves more plaudits, and he and the likes of him in Europe like Gasperini, are already put on a pedestal, but managerial magnates like Pep Guardiola, and Jose Mourinho, to name a few. This article does a brilliant job, referring to the role of politics within the belief systems of top coaches, namely Bielsa in this case, and more, and thus humanise these stalwarts. Cheers!