Ravichandran Ashwin begins the fifth chapter of his autobiography, I Have The Streets, with a kutti (small) story.

Young Ashwin was a batter. Like many from his generation, he too dreamt of one day striding out to a pitch alongside Sachin Tendulkar. At the India U-17 selection camp, he arrived as a proper batsman who could, if needed, send down some medium-pace deliveries. His roommate at the camp was Anirudha Srikkanth, son of World Cup-winner Krishnamachari Srikkanth, and Ashwin’s captain in the Tamil Nadu U-17 team.

Something about Ashwin’s bowling caught Anirudha’s eye - not the medium pace, mind you, but the spin. In competitive games, Anirudha kept calling on Ashwin for bowling duties, bypassing other frontline bowlers. And Ashwin responded, in his own way.

“Anirudha, though, loves me to bits for my bowling,” Ashwin writes. “I don’t know why. Even when he wasn’t the captain, he would keep asking the captain to bring me on to bowl. Perhaps he is just amused, or perhaps he has his father’s eye for talent. Amused because I am constantly changing my actions. Sometimes I bowl offspin; on the odd occasion, I bowl legspin with the same action.”

The reason for this variety - at his callow, carefree age - could come across as vibes. Ashwin hadn’t begun taking his spin-bowling seriously at the time. Besides, most young cricketers at this stage are like freshly-minted poets, drunk on the music of their own talent, yet to master rhythm or meter. They play cricket like they breathe - naturally, unthinkingly. The intellectual polish, the forensic understanding, that comes later.

Ashwin then adds a key detail: “But I invariably get him wickets. Every time he gives me the ball, I pick up wickets. Before lunch, before tea, before drinks, whenever.”

For the next two paragraphs, Ashwin drops into a dissertation on field placements and batting psychology. One realises early into the book that this academic curiosity towards his sport - something that we now recognise him with - was part of his DNA.

Spin bowling is deception dealt in daylight. The spinner’s art lives in those microscopic adjustments - a fraction higher, a touch slower, a seam angled just so. Unlike fast-bowling, spin is not about overwhelming the senses, but seducing them.

For practitioners of off-spin, like Ashwin, this deception becomes even more crucial. While the leg-spinner’s art has natural misdirection - the ball breaking away from its apparent path - an off-spinner turns the ball exactly where logic dictates, and yet must find ways to create mystery.

The art of spin lives in that space between what is shown and what is hidden, in the gentle craft that makes its home in nuance rather than force.

And yet, we look suspiciously at those who chase nuance, don’t we? We like “naturals”, artists who make things happen by pure genius. We have pejoratives for those who spend too long studying the theory behind why the chord progression in the bridge section of Comfortably Numb works as well as it does.

Cricket has always had its intellectuals, but they usually kept their nerdery private. Consider Erapalli Prasanna - in many ways, Ashwin’s true predecessor, and one of India’s forgotten greats. When asked about his 189 Test wickets and how many were carefully planned, he responded with, “Around 160.”

Ashwin wears the tag of cricket’s biggest, hungriest nerd like a badge of honour.

A week and a bit back, Gukesh Dommaraju became the youngest ever chess world champion. He outdid Gary Kasparov, Magnus Carlsen, and our very own, Viswanathan Anand.

I have been thinking about chess since. My abilities are limited, by which I mean they don’t exist. I can probably guess which direction a piece can move in, but that’s about it. If you sit across from me at a chessboard, you will finish me before you finish your filter coffee.

That said, I truly appreciate what chess stands for and what it takes to be good at it. I love that it celebrates what many other sports treat with mild derision: the marriage of intellect and obsession, the beautiful necessity of deep knowledge. It’s where the nerd isn't just tolerated but elevated.

I don’t know if Ashwin likes chess, but I have no doubt that he would’ve been a champion. He might just start now and become really good. After all, Ashwin’s approach to cricket has carried some peak Chess Player Energy™.

Chess players are excellent problem-solvers. From the kindergarten of his international career, Ashwin was often thrown into problems, carrying an expectation to come up with solutions.

Barely a year into his international career, he was bowling to Shane Watson in a World Cup quarter-final. He was specifically chosen for that battle, and he won it. Within a couple of months more, he was put against Chris Gayle at the Indian Premier League final, in the first over of the chase, without the luxury of protection from Gayle’s explosive instincts. He won that battle too. He sent two loopy off-spinners that turned away before bowling a straighter one that Gayle was late at adjusting to. Ashwin finished that final with 4 overs, 16 runs, 3 wickets.

Ashwin made his Test debut later that year. Imagine the shoes he was filling. Anil Kumble had retired a few years back, and Harbhajan Singh was in sight of his finish line, if not close to it. India’s lineage of batting is often spoken about, rightly so, but India’s lineage of spin-bowling is equally daunting. You have to be excellent to come, exceptional to stay.

The rest of the team, too, was in transition - the entire generation of Tendulkar, Dravid, Laxman and others were slowly moving out. Ashwin won the Player of the Match on his debut and finished that series with the Player of the Series award.

Within six months, after one wicketless game at Sydney, he was dropped from the Test team. He was 25, on his first tour to Australia, but it didn’t matter.

That Sydney Test became ground zero for a worrying trend with Ashwin - we began discussing him through the lens of what he couldn’t do, instead of celebrating all he could. The discourse started with his fitness. He didn’t look like what everyone thought a professional cricketer should, so it became a convenient stick to whack him with.

This was the era when Indian cricket was still undergoing a physical metamorphosis. John Wright, India’s former coach, once walked into a training session to find players pre-gaming with copious cups of chai. Their kit bags were being carried around by helpers.

Wright, along with physio Andrew Leipus, introduced a culture of fitness that transformed Indian cricket. In Sourav Ganguly - and then Rahul Dravid, Anil Kumble, and MS Dhoni - India found captains who bought into the importance of athleticism to succeed in 21st-century cricket. Players became leaner, faster, stronger. And India went from a side that couldn’t field or run, to one that had some of the sharpest fielders and quickest runners in the world.

That influence trickled down to domestic and age-group cricket. Coaches started calling junior players out on double chins, and reporters were keen to write about it every time they sniffed a chance.

In his book, Ashwin recalls the lazy and pointed discussion about his body-type during his junior cricket days.

“Even when I make it to the newspaper articles, the last paragraph makes a reference to my waistline, pointing out that I need to shed weight to make it to the next level.”

Yet he kept advancing, level after level, even as he stood surrounded by natural athletes. It was Anirudha Srikkanth at state-level, and then Jadeja, Kohli, Dhoni, Dhawan, Rohit - you name it - once he got his India cap. All of them could sprint like panthers prowling the Serengeti. Ashwin, well, let's just say panther isn’t the animal you think of when you see him run.

But, here’s the truth: what Ashwin lacked in athleticism, he more than made up for it with application. He was cricket-fit. Fit enough to become the backbone for India’s new, young team to begin building a fortress at home. Fit enough to become a bowling weapon who helped push India to a World T20 final. Fit enough to become ICC Cricketer of The Year in a year when the face of the sport, Virat Kohli, scored big runs practically every time he walked out to bat. Fit enough to become the fastest Indian bowler to 100, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, 450, and 500 Test wickets.

For all the talk of Indian conditions helping spinners, there is very little discussion about the unforgiving weather they often play under. The Test season is scheduled during late-autumn and winter, but try stepping outside on a November afternoon in Chennai or Mumbai, and you will realise that winter is often just a rumour in some Indian cities.

If you want a testament to Ashwin’s fitness, how about this - he did not miss a single home Test across his career. Not dropped, never got injured.

There’s more. Of course, there is more.

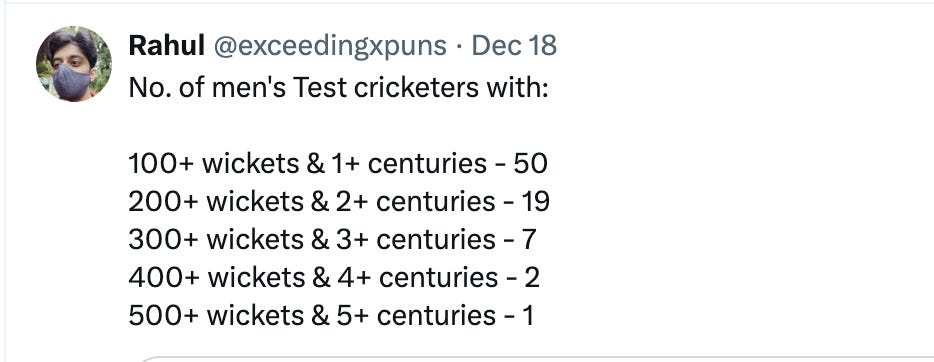

Ashwin played out a career as a bowler, and yet, finished with a place in history no other all-rounder has yet claimed.

A total of nine cricketers have taken 500 Test wickets. All of them, combined, have 7 Test centuries, 6 of which have been scored by Ravichandran Ashwin.

Ashwin was fit enough, and good enough, to go back to Australia and play a key part - with ball and bat - in two seminal series wins. On the same Sydney Cricket Ground where he was once deemed good but not enough, he woke up on Day Five with a back that refused to function, had to be practically carried from his bed to the shower, but found enough strength to drape his India whites and bat for four hours to save a match and the series.

On that tour, Ashwin was also India’s weapon of choice with the ball to neutralise Australia’s best batters. Yet, on the first morning of these matches, as the team news wafted through the media centre to the news outlets, you could hear groans and doubts about him. Can he?

Truth be told, there was empirical evidence of him losing sharpness outside the subcontinent, and the questions were based on those immediately-accessible numbers. But myopia blurs things outside a close field of vision, which is possibly why it was hard to pay attention to Ashwin’s habit of constant learning and reinvention. He found a way.

Success, especially in a team sport, depends on many things falling into place, but we were uncomfortable with even giving him a chance.

He spent long hours with bowling coaches and analysts, obsessing over data and videos, just to conquer the patch that seemed elusive. It wasn’t so much a special effort as it was Ashwin being Ashwin. During a lovely interview with Siddharth Monga in December 2021, Ashwin let us peek into his obsession.

“When England came to India, I watched their whole Sri Lanka series without missing one ball. I would immediately go back to Hari [the India analyst] and ask him what speed [Lasith] Embuldeniya was bowling, what speed Dilruwan [Perera] was bowling, what percentage of balls were within the stumps. We have this app where we can sort, so I watched again all the Dilruwan Perera videos.

I will watch every single ball. And I will watch slow-mo, super slow-mo. I try and see if I can dissect it. If there are differences in triggers, use split-screen. If I'm not able to entirely dissect it, I go to Hari and ask him to put a split screen on Ball A, Ball B, Ball C.”

Ashwin could have coasted on his natural gifts, but that would have been antithetical to his nature. He always wanted to keep pushing the boundaries of what he could do as a cricketer.

He thought like that when his Under-17 captain passed him the ball at a state match, and he was in the same zone at the age of 38, in a series he likely knew would be his last.

A couple of days before the second Test of the ongoing series between Australia and India, he sought out journalist Bharat Sundaresan.

“The early part of our interaction was all match-related. About players in the Sheffield Shield and their performances. He also wanted to know where he could find highlights of the last Shield game that had been played at the Adelaide Oval prior to the Test.”

**

Rumours began flying early on the final morning of the Brisbane Test between Australia and India. Twitter was abuzz. Someone significant was stepping away.

Given the timing - middle of an important tour - and the hierarchy of batters and bowlers in Indian cricket, the shortlist quickly went from three to one. And when the broadcasters showed Ashwin in an emotional conversation with Virat Kohli, the last wisps of fog cleared up.

Before we could process the confirmation, Ashwin was going up an elevator to address the post-match press conference. The speech was brief - a quick announcement and thanks - and he was gone. Poof! The next day, he was on a flight back to Chennai.

For a souvenir, we got a video from the India dressing room, set to an emotional background score of piano and violins, where Ashwin addresses the team. He finishes with, “I am so happy today.”

He has every reason to be. He extracted every ounce of performance from his potential, and then found other sources of energy.

There’s something about Ashwin that makes people uncomfortable. Perhaps it’s the way he speaks - direct, unfiltered, with the confidence of someone who knows exactly how good he is. Perhaps it’s his methods - the analytical mind, his love for variation and experimentation, the intellectual approach to a role that many believe should be guided purely by instinct. Or perhaps it’s simply that he doesn’t fit into the neat boxes we’ve created for our cricketers.

Ashwin’s story is as much a credit to what Indian cricket can conjure up as it is an indictment of what it never truly values. He spent an entire career having to prove his worth. By the end, one assumes that a sample of 765 international wickets and 4394 international runs is enough to judge that he ended up on the right side of that conversation.

“I'll say again that I never expected Ashwin to become what he is today. He wasn't genetically gifted like an Usain Bolt or a Michael Phelps. He was just a middle-class boy who had the smarts to become a doctor or an accountant - or the engineer he eventually became. He had no business becoming an elite athlete and one of the best at that. It meant taking the road less travelled, using every inch of an advantage he could get, and trying to innovate and adapt all the time. I said this once on commentary: R Ashwin is like your latest smartphone; his software is always up to date.” - Abhinav Mukund

The timing of Ashwin’s departure raises its own questions, and perhaps there’s no greater tribute to Ashwin the cricketer and thinker than leaving us with that uncertainty. Even as his body began groaning, even as age chipped away at his knees, Ashwin was one step ahead of the opposition. It says something that, in his final Test series, on pitches that had absolutely nothing for spinners, Ashwin looked the most threatening of all his peers.

Was he in the evening of his career? Sure. Was he done? Guess we’ll never know.

In his post-retirement interviews, Ashwin has mentioned that he wants to play a lot of club-level and IPL cricket. If this is the commencement of his unhinged arc, we are in for a ride. At long last, Ashwin can unburden himself from the anxiety and grind of being Ashwin.

Few cricketers can claim to have elevated their craft to new dimensions, but Ravichandran Ashwin did so while simultaneously raising the discourse around it, often without adequate applause.

Either way, he had the streets. Always will.

Video credit: Cricanimations.

Love it. I am always surprised by how much i can learn from each of your articles!

Beautifully written. But somehow no one is willing to go into the “Why” of Ashwin being asked to constantly prove himself. Feel he could turn out to be a captain of an IPL team